This article gives simple and practical guidance to managers, supervisors and operators on how-to recognize and deal with typical human-factor problems involving alarm systems in the Oil & Gas, Power Plants, Refineries, chemical and allied industries. It aims to prevent future accidents.

Control Room Alarm Management

Here is a step-by-step approach for improving alarm handling; as with managing any other risk: firstly, identify any problems; secondly, plan what to do; and thirdly, eliminate or control them.

STEP 1: FIND OUT IF YOU HAVE A PROBLEM

Are there problems with the existing alarm system?

Take some measurements to find out:

- How many alarms are there?

- Are they all necessary, requiring operator action?

(Note: process status indicators should not be designated as alarms.) - How many alarms occur during normal operation?

- How many occur during a plant upset?

- How many standing alarms are there?

Alarm rate targets: the long-term average alarm rate during normal operation should be no more than one every ten minutes; and no more than ten displayed in the first ten minutes following a major plant upset.

Ask operators and safety representatives about their experiences:

- Are they ever overwhelmed by alarm ‘floods’?

- Are there nuisance alarms, eg are large numbers of alarms acknowledged in quick succession, or are audible alarms regularly turned off?

- Is alarm prioritization helpful?

- Do they know what to do with each alarm?

- Are the control room displays well laid out and easy to understand?

- Is clear help available, written or on-screen?

- How easy is it to ‘navigate’ around the alarm pages?

- Are the terms used on screen the same as the operators use?

For effective alarm prioritization:

- Define prioritization rules and apply them consistently to each alarm in every system.

- Use about three priorities.

- Base priorities on the potential consequences if the operator fails to respond.

- Prioritize proportionately, eg 5% high priority, 15% medium, and 80% low.

Ask managers about alarm issues, eg:

- Have there been any critical incidents or near misses where operators missed alarms or made the wrong response?

- Is there a written policy/strategy on alarms?

- Is there a company standard on alarms?

How are new alarms added and existing ones modified? Is there a structured process for this?

For example there is a tendency for hazard and operability studies (HAZOPs) to generate actions which result in a lot of ‘quick fix’ alarms being installed.

- How many new alarms did your last HAZOP produce and how were they justified?

- Can the operators notice and respond correctly to them? Was the impact on the overall alarm burden on operators considered?

Operator Reliability

High operator reliability requires:

- very obvious display of the specific alarm;

- few false alarms;

- a low operator workload;

- a simple well-defined operator response;

- well trained operators;

- testing of the effectiveness of operators responses.

Can you demonstrate you have achieved this level of reliability, eg in safety reports and risk assessments, do you make unreasonable claims for the likelihood of operators responding correctly to alarms?

Is the alarm system designed to a standard that takes human limitations into account?

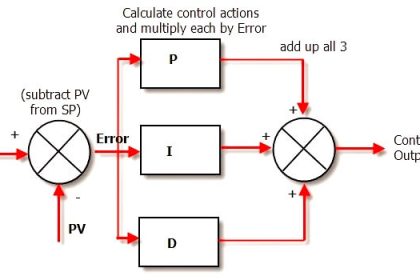

An effective alarm system should ‘direct the operator’s attention towards plant conditions requiring timely assessment or action and so should:

- Alert, inform and guide the operators, allowing them to diagnose problems and keep the process within its ‘safe envelope’.

- Prevent unnecessary emergency shutdown.

- Only present the operator with useful and relevant alarms.

- Use prioritization to highlight critical alarms.

- Have a defined response to each alarm.

- Be ergonomically designed to meet user needs and capabilities.

- Allow enough time for the operator to respond.

STEP 2: DECIDE WHAT TO DO AND TAKE ACTION

Form a team to progress the issues:

The team should include the right technical, operational and safety representatives. Relate identified problems back to the overall plant risk assessments.

Decide which ones present the biggest risks, and produce a timed action plan to deal with them. Identify and agree the necessary resources but be careful not to underestimate the effort involved.

A quick first-pass review may cover perhaps 50 alarms per shift but a thorough review and redesign may take more than 1 shift per alarm.

One company reviewed their alarm system after an incident and found it had poorly prioritized and designed alarms resulting in high alarm rates. They set up a project to review existing systems. It was run by a steering committee with a senior management ‘champion’. A multidisciplinary team, including operators, carried out the work.

They identified best practice and rolled out an action programme to:

- reduce the number of standing alarms;

- set rules for deciding priority levels;

- provide operator diagnostic training;

- set a standard for maximum alarm rates;

- implement alarm-filter techniques; and

- produce a site alarm strategy document and an engineering specification for future projects.

The steering committee continued to review progress and strategy.

Implement some quick and relatively easy technical solutions that can provide immediate benefits for operators:

- eliminate/review alarms with no defined operator response, or which are not understood;

- tune alarm settings on nuisance alarms;

- adjust deadbands on repeating alarms.

- suppress alarms from out-of-service plant;

- re-engineer repeating alarms; and

- replace digital alarm sensors causing nuisance with analogue sensors.

Establish operating team competency:

- Is their training adequate, realistic, and based on an analysis of the actual work carried out?

- Is their competence tested?

Well-designed simulators and simulator training can be very effective if properly integrated into the training program m e. Ensure that training is sufficiently realistic for both normal and abnormal conditions.

Provide operators with sufficient help and support to respond effectively to alarms:

- Do displays and on-line help present alarm information in the best way, eg coloured mimics instead of alarm lists?

- Are roles and responsibilities clear for normal and abnormal conditions?

- Are there enough operators and supervisors to manage upsets properly, and are they there when needed?

STEP 3: CHECK AND MANAGE WHAT YOU HAVE DONE

Improving alarm handling is not a one-off project. You now need to manage it in a systematic way as part of your normal safety or quality assurance management system to maintain control and ownership.

For example: Draw up a site/company alarm strategy and standard. The strategy should include a clear definition and purpose for all site alarms, a commitment to suitable training and reviews, and to ergonomic design. The standard should include a mechanism for regular review and alarm change-control, definitions of responsibilities, operator training requirements, etc.

Checking: This includes formal audits and reviews, consultation with safety representatives, informal feedback from operators and supervisors. For example, the original measurements already carried out (see Step 1) can be repeated to measure progress and to see if performance is now reasonable. The alarm steering committee (or its equivalent) has an ongoing role in this process.

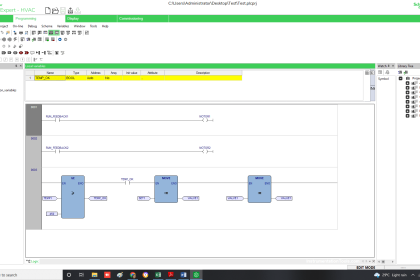

Design of new alarm systems: Much of what we have written here is about improving an existing alarm system. It is better to design the alarm system right in the first place. Your alarm standard should be used to set suitable specifications for purchasing alarm system equipment.

Conclusion

Better alarm handling can have a significant effect on the safety of your business (the cost of not improving alarm handling can literally be your business in some cases).

An improved alarm system can bring tighter quality control, improved fault diagnosis and more effective plant management by operators.

A number of quick and relatively easy technical solutions are available which can bring immediate benefits. Medium and longer-term programmes can bring greater benefits still.

Note : Contains public sector information licensed under Open Government Licence v3.0.

Definition of the term “alarm” ?

The concept of alarms (French for “a l’arme” which means “spring to arms”) is very old and originates from the military concept where a guard warns his fellows in case of an attack. In process control, alarms have a very long tradition as well (e.g., a whistle indicating that water is boiling) and have evolved over time with older plants were using panels with bulbs and bells to alert the operators to large screen displays full of information.

However, in today’s control room we often encounter the situation where the operators are flooded with too many alarms. Hence making it difficult to decide where to focus their actions.

Historically, the configuration of the Panel Boards has been expensive, because each alarm required extra hardware and wiring. Therefore the designers of a control room put considerable thought in the decision of whether an alarm was meaningful or not. This form of implicit alarm management often resulted in good quality operator interfaces.

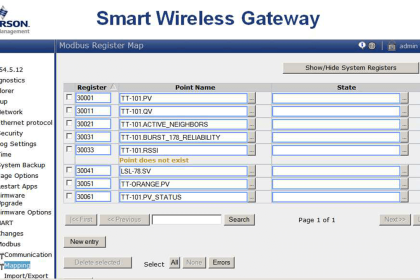

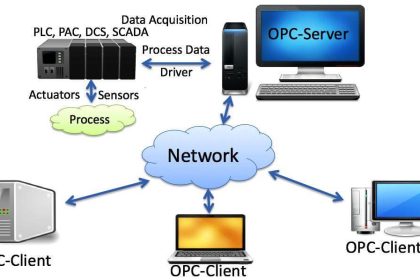

With the introduction of computerized control systems like the current generation of Supervisor Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, the cost associated with alarm configuration has been significantly reduced. Therefore, it is easy to configure several alarms on each and every point.

Engineers tend to hesitate before removing an alarm when unsure if the alarm is relevant. Modern field devices are able to generate a multitude of diagnostic messages, many of them issued as alarms. This typically results in huge amounts of configured alarms. As a consequence, during operation, operators receive huge amounts of alarms, even during normal operation.

Today it is very common to receive more than 2,000 alarms a day per operator. Most of those alarms are nuisance alarms that provide no value for the operators.

Definition of the term “alarm” according to ISA-18.2 ?

The definition means that an alarm must indicate a problem, not a normal process condition. The target audience of an alarm should be operators, not engineers, maintenance technicians, or managers.

Today’s reality in many control rooms is different: most of the occurring alarms have little or no value for the operators.

Great

Tnx