A common phrase heard in reference to electrical safety goes something like this: ”It’s not the voltage that kills, its current!” While there is an element of truth to this, there’s more to understand about shock hazard than this simple adage. If the voltage presented no danger, no one would ever print and display signs saying:

DANGER – HIGH VOLTAGE!

The principle that ”current kills” is essentially correct. It is the electric current that burns tissue, freezes muscles, and fibrillates hearts. However, electric current doesn’t just occur on its own: there must be voltage available to motivate electrons to flow through a victim. A person’s body also presents resistance to the current, which must be taken into account.

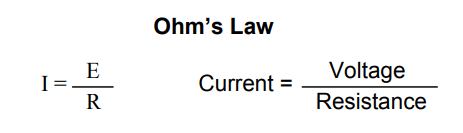

Ohm’s Law

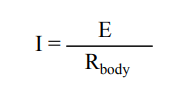

Taking Ohm’s Law for voltage, current, and resistance, and expressing it in terms of current for a given voltage and resistance, we have this equation:

The amount of current through a body is equal to the amount of voltage applied between two points on that body, divided by the electrical resistance offered by the body between those two points. Obviously, the more voltage available to cause electrons to flow, the easier they will flow through any given amount of resistance. Hence, the danger of high voltage: high voltage means potential for large amounts of current through your body, which will injure or kill you.

Conversely, the more resistance a body offers to current, the slower electrons will flow for any given amount of voltage. Just how much voltage is dangerous depends on how much total resistance is in the circuit to oppose the flow of electrons.

Body resistance is not a fixed quantity. It varies from person to person and from time to time. There’s even a body fat measurement technique based on a measurement of electrical resistance between a person’s toes and fingers. Differing percentages of body fat give provide different resistances: just one variable affecting electrical resistance in the human body. In order for the technique to work accurately, the person must regulate their fluid intake for several hours prior to the test, indicating that body hydration is another factor impacting the body’s electrical resistance.

Body resistance also varies depending on how contact is made with the skin: is it from hand-to-hand, hand-to-foot, foot-to-foot, hand-to-elbow, etc.? Sweat, being rich in salts and minerals, is an excellent conductor of electricity for being a liquid. So is blood, with its similarly high content of conductive chemicals. Thus, contact with a wire made by a sweaty hand or open wound will offer much less resistance to current than contact made by clean, dry skin.

Measuring electrical resistance with a sensitive meter, I measure approximately 1 million ohms of resistance (1 MΩ) between my two hands, holding on to the meter’s metal probes between my fingers. The meter indicates less resistance when I squeeze the probes tightly and more resistance when I hold them loosely.

Sitting here at my computer, typing these words, my hands are clean and dry. If I were working in some hot, dirty, industrial environment, the resistance between my hands would likely be much less, presenting less opposition to deadly current, and a greater threat of electrical shock.

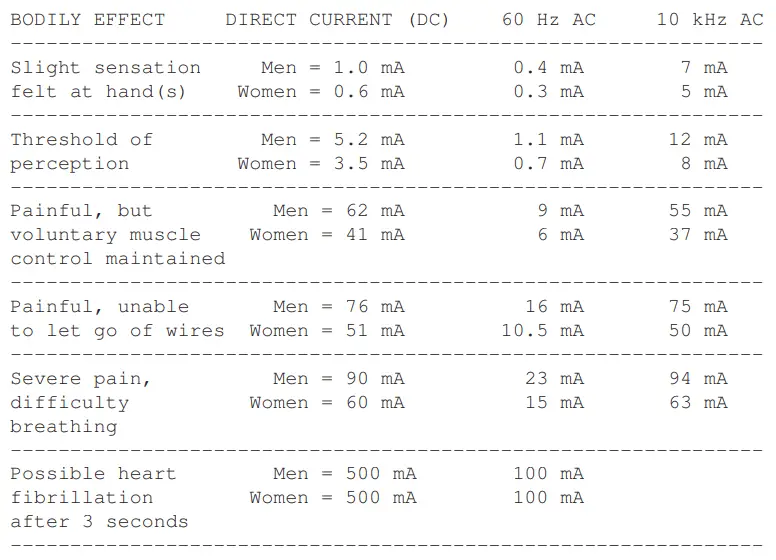

But how much current is harmful? The answer to that question also depends on several factors. Individual body chemistry has a significant impact on how electric current affects an individual. Some people are highly sensitive to current, experiencing involuntary muscle contraction with shocks from static electricity.

Others can draw large sparks from discharging static electricity and hardly feel it, much less experience a muscle spasm. Despite these differences, approximate guidelines have been developed through tests which indicate very little current being necessary to manifest harmful effects (again, see end of chapter for information on the source of this data).

All current figures given in milliamps (a milliamp is equal to 1/1000 of an amp):

Effects of Current on Human Body

”Hz” stands for the unit of Hertz, the measure of how rapidly alternating current alternates, a measure otherwise known as frequency. So, the column of figures labeled ”60 Hz AC” refers to current that alternates at a frequency of 60 cycles (1 cycle = period of time where electrons flow one direction, then the other direction) per second.

The last column, labeled ”10 kHz AC,” refers to alternating current that completes ten thousand (10,000) back-and-forth cycles each and every second.

Keep in mind that these figures are only approximate, as individuals with different body chemistry may react differently. It has been suggested that an across-the-chest current of only 17 milliamps AC is enough to induce fibrillation in a human subject under certain conditions.

Most of our data regarding induced fibrillation comes from animal testing. Obviously, it is not practical to perform tests of induced ventricular fibrillation on human subjects, so the available data is sketchy. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, I have no idea why women tend to be more susceptible to electric currents than men!

Suppose I were to place my two hands across the terminals of an AC voltage source at 60 Hz (60 cycles, or alternations back-and-forth, per second). How much voltage would be necessary in this clean, dry state of skin condition to produce a current of 20 milliamps (enough to cause me to become unable to let go of the voltage source)? We can use Ohm’s Law (E=IR) to determine this:

E = IR

E = (20 mA)(1 MΩ)

E = 20,000 volts, or 20 kV

Bear in mind that this is a ”best case” scenario (clean, dry skin) from the standpoint of electrical safety, and that this figure for voltage represents the amount necessary to induce tetanus. Far less would be required to cause a painful shock! Also keep in mind that the physiological effects of any particular amount of current can vary significantly from person to person, and that these calculations are rough estimates only.

With water sprinkled on my fingers to simulate sweat, I was able to measure a hand-to-hand resistance of only 17,000 ohms (17 kΩ). Bear in mind this is only with one finger of each hand contacting a thin metal wire. Recalculating the voltage required to cause a current of 20 milliamps, we obtain this figure:

E = IR

E = (20 mA)(17 kΩ)

E = 340 volts

In this realistic condition, it would only take 340 volts of potential from one of my hands to the other to cause 20 milliamps of current. However, it is still possible to receive a deadly shock from less voltage than this.

Provided a much lower body resistance figure augmented by contact with a ring (a band of gold wrapped around the circumference of one’s finger makes an excellent contact point for electrical shock) or full contact with a large metal object such as a pipe or metal handle of a tool, the body resistance figure could drop as low as 1,000 ohms (1 kΩ), allowing an even lower voltage to present a potential hazard:

E = IR

E = (20 mA)(1 kΩ)

E = 20 volts

Notice that in this condition, 20 volts is enough to produce a current of 20 milliamps through a person: enough to induce tetanus. Remember, it has been suggested a current of only 17 milliamps may induce ventricular (heart) fibrillation. With a hand-to-hand resistance of 1000 Ω, it would only take 17 volts to create this dangerous condition:

E = IR

E = (17 mA)(1 kΩ)

E = 17 volts

Seventeen volts is not very much as far as electrical systems are concerned. Granted, this is a ”worst-case” scenario with 60 Hz AC voltage and excellent bodily conductivity, but it does stand to show how little voltage may present a serious threat under certain conditions.

The conditions necessary to produce 1,000 Ω of body resistance don’t have to be as extreme as what was presented, either (sweaty skin with contact made on a gold ring). Body resistance may decrease with the application of voltage (especially if tetanus causes the victim to maintain a tighter grip on a conductor) so that with constant voltage a shock may increase in severity after initial contact. What begins as a mild shock – just enough to ”freeze” a victim so they can’t let go – may escalate into something severe enough to kill them as their body resistance decreases and current correspondingly increases.

Research has provided an approximate set of figures for electrical resistance of human contact points under different conditions (see end of chapter for information on the source of this data):

- Wire touched by finger: 40,000 Ω to 1,000,000 Ω dry, 4,000 Ω to 15,000 Ω wet.

- Wire held by hand: 15,000 Ω to 50,000 Ω dry, 3,000 Ω to 5,000 Ω wet.

- Metal pliers held by hand: 5,000 Ω to 10,000 Ω dry, 1,000 Ω to 3,000 Ω wet.

- Contact with palm of hand: 3,000 Ω to 8,000 Ω dry, 1,000 Ω to 2,000 Ω wet.

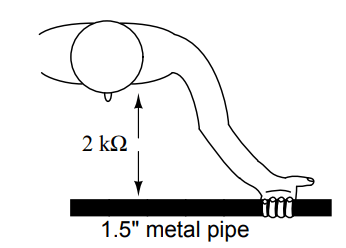

- 1.5 inch metal pipe grasped by one hand: 1,000 Ω to 3,000 Ω dry, 500 Ω to 1,500 Ω wet.

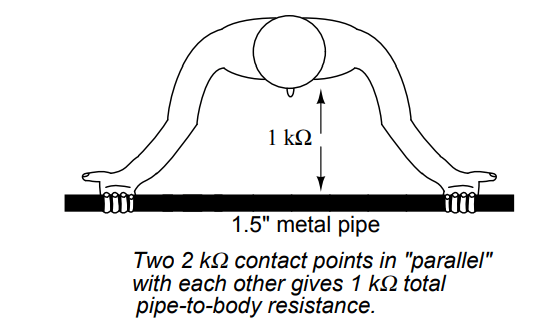

- 1.5 inch metal pipe grasped by two hands: 500 Ω to 1,500 kΩ dry, 250 Ω to 750 Ω wet.

- Hand immersed in conductive liquid: 200 Ω to 500 Ω.

- Foot immersed in conductive liquid: 100 Ω to 300 Ω.

Note the resistance values of the two conditions involving a 1.5 inch metal pipe. The resistance measured with two hands grasping the pipe is exactly one-half the resistance of one hand grasping the pipe.

With two hands, the bodily contact area is twice as great as with one hand. This is an important lesson to learn: electrical resistance between any contacting objects diminishes with increased contact area, all other factors being equal.

With two hands holding the pipe, electrons have two, parallel routes through which to flow from the pipe to the body (or vice-versa).

As we will see in a later chapter, parallel circuit pathways always result in less overall resistance than any single pathway considered alone.

In industry, 30 volts is generally considered to be a conservative threshold value for dangerous voltage. The cautious person should regard any voltage above 30 volts as threatening, not relying on normal body resistance for protection against shock. That being said, it is still an excellent idea to keep one’s hands clean and dry, and remove all metal jewelry when working around electricity.

Even around lower voltages, metal jewelry can present a hazard by conducting enough current to burn the skin if brought into contact between two points in a circuit. Metal rings, especially, have been the cause of more than a few burnt fingers by bridging between points in a low-voltage, high-current circuit.

Also, voltages lower than 30 can be dangerous if they are enough to induce an unpleasant sensation, which may cause you to jerk and accidently come into contact across a higher voltage or some other hazard. I recall once working on a automobile on a hot summer day. I was wearing shorts, my bare leg contacting the chrome bumper of the vehicle as I tightened battery connections.

When I touched my metal wrench to the positive (ungrounded) side of the 12 volt battery, I could feel a tingling sensation at the point where my leg was touching the bumper. The combination of firm contact with metal and my sweaty skin made it possible to feel a shock with only 12 volts of electrical potential.

Thankfully, nothing bad happened, but had the engine been running and the shock felt at my hand instead of my leg, I might have reflexively jerked my arm into the path of the rotating fan, or dropped the metal wrench across the battery terminals (producing large amounts of current through the wrench with lots of accompanying sparks). This illustrates another important lesson regarding electrical safety; that electric current itself may be an indirect cause of injury by causing you to jump or spasm parts of your body into harm’s way.

The path current takes through the human body makes a difference as to how harmful it is. Current will affect whatever muscles are in its path, and since the heart and lung (diaphragm) muscles are probably the most critical to one’s survival, shock paths traversing the chest are the most dangerous. This makes the hand-to-hand shock current path a very likely mode of injury and fatality.

To guard against such an occurrence, it is advisable to only use one hand to work on live circuits of hazardous voltage, keeping the other hand tucked into a pocket so as to not accidently touch anything. Of course, it is always safer to work on a circuit when it is unpowered, but this is not always practical or possible. For one-handed work, the right hand is generally preferred over the left for two reasons: most people are right-handed (thus granting additional coordination when working), and the heart is usually situated to the left of center in the chest cavity.

For those who are left-handed, this advice may not be the best. If such a person is sufficiently uncoordinated with their right hand, they may be placing themselves in greater danger by using the hand they’re least comfortable with, even if shock current through that hand might present more of a hazard to their heart. The relative hazard between shock through one hand or the other is probably less than the hazard of working with less than optimal coordination, so the choice of which hand to work with is best left to the individual.

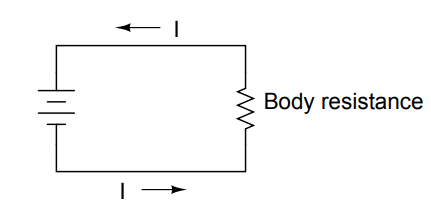

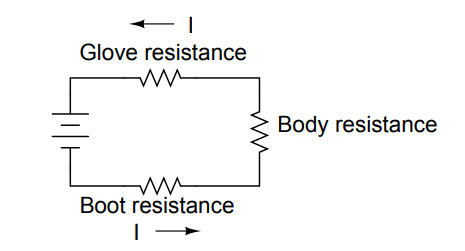

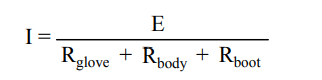

The best protection against shock from a live circuit is resistance, and resistance can be added to the body through the use of insulated tools, gloves, boots, and other gear. Current in a circuit is a function of available voltage divided by the total resistance in the path of the flow. As we will investigate in greater detail later in this book, resistances have an additive effect when they’re stacked up so that there’s only one path for electrons to flow:

Person in direct contact with voltage source:

Current limited only by body resistance.

Now we’ll see an equivalent circuit for a person wearing insulated gloves and boots:

Person wearing insulating gloves and boots:

current now limited by total circuit resistance.

Because electric current must pass through the boot and the body and the glove to complete its circuit back to the battery, the combined total (sum) of these resistances opposes the flow of electrons to a greater degree than any of the resistances considered individually.

Safety is one of the reasons electrical wires are usually covered with plastic or rubber insulation: to vastly increase the amount of resistance between the conductor and whoever or whatever might contact it. Unfortunately, it would be prohibitively expensive to enclose power line conductors in sufficient insulation to provide safety in case of accidental contact, so safety is maintained by keeping those lines far enough out of reach so that no one can accidently touch them.

Review:

- Harm to the body is a function of the amount of shock current. Higher voltage allows for the production of higher, more dangerous currents. Resistance opposes current, making high resistance a good protective measure against shock.

- Any voltage above 30 is generally considered to be capable of delivering dangerous shock currents.

- Metal jewelry is definitely bad to wear when working around electric circuits. Rings, watchbands, necklaces, bracelets, and other such adornments provide excellent electrical contact with your body, and can conduct current themselves enough to produce skin burns, even with low voltages.

- Low voltages can still be dangerous even if they’re too low to directly cause shock injury. They may be enough to startle the victim, causing them to jerk back and contact something more dangerous in the near vicinity.

- When necessary to work on a ”live” circuit, it is best to perform the work with one hand so as to prevent a deadly hand-to-hand (through the chest) shock current path.